Every pupil at Cedars School of Excellence, in Greenock, Scotland, is now armed with an iPad, creating an environment a world away from the typical 'computer room', and providing the potential for seamless integration of technology and traditional teaching.

The iPad project arose from day-to-day demands within the school. As Head of Computing, a dozen iMacs were fixed in Fraser's classroom, and a dozen MacBooks were available for booking; but with teachers increasingly wanting to provide pupils with web access, pressure and demand grew.

"In January 2010, we started looking for answers," recalls Fraser. The school couldn't afford enough laptops to make a meaningful difference, but the iPod touch was considered, since internet access was a big factor. "We realised the iPod touch was cheap enough to give one to everybody," says Fraser, "but teachers had issues with what it couldn't do."

At the time, the iPod touch couldn't output to a projector nor connect to a mechanical keyboard, but the school nonetheless continued forming its plans. And then the iPad arrived.

Fraser says Apple's tablet dealt with every problem the school had with the iPod touch: it boasted a decent software keyboard and projector connection, and Apple made office apps available for sale. On importing his own iPad from the US, Fraser was sold:

"On the first day, it ran and ran. I couldn't make the battery die, and I realised this alone would transform the technology experience in the classroom."

With many of the school's teachers being iPhone owners, few needed convincing. A leasing arrangement with the local Apple Store soon saw dozens of iPads winging their way to Greenock. (Fraser notes that leasing was done through the Glasgow Apple Store's business team, and isn't a special school lease.)

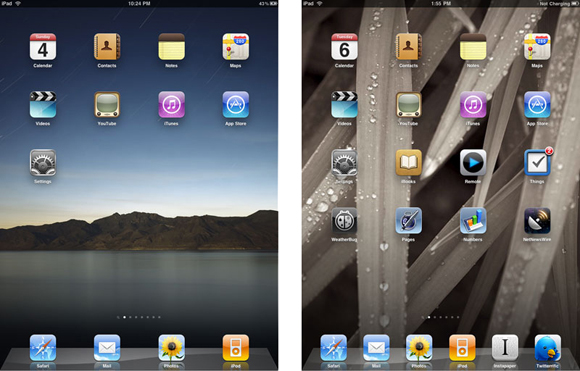

Even teachers who weren't confident with technology and didn't see a place for their laptops in school started bringing their iPads with them every day, and everyone found different ways for Apple's tablet to enhance their classes. Ultimately, this is driven by the blank-slate aspect of the iPad.

"This is a device we bought, but it's not just a textbook or an instrument, or a set of art tools – it's all of those things and more," says Fraser, adding that one teacher's putting together a band, purely comprising children playing iPad apps.

"The thing is, to do this we're not adding anything to the classroom – it's just more software on the devices." When the discussion turns to specific use-scenarios for the iPad, it's clear Apple's 'there's an app for that' approach could revolutionise the classroom. For infants, the school uses the likes of wood-puzzle-style apps to develop motor skills, abc PocketPhonics for tracing letters, and Math Bingo (which Fraser calls a "sensational hit") for basic maths.

Elsewhere, older pupils are immersed in iBooks, which replaces the class's paper books with eBooks, and Keynote for presentations. And with any child aged 10 or older allowed to take their iPad home, homework is sent and received via email; this enables teachers to set more flexible tasks in sensible chunks, eliminates most excuses and has reduced the amount of incomplete homework.

Interestingly, many apps are also being used in new and innovative ways. For example, Fraser says Numbers is employed in situations where people may not have reached for a spreadsheet before, such as to create formulae for testing expected output in programming classes, or for capturing live information about experiments as they progress.

The nature of the App Store helps, providing countless specialised apps that can be used to teach a particular aspect of a course. In his computing class, Fraser has utilised the game Binary Madness HD, which has you convert random decimal numbers to binary as quickly as possible: "It's not something I use every day, but small apps like this reinforce specific parts of learning."

He rightly adds this is something that you rarely find on other platforms: "No-one would write a Mac app like Binary Madness HD, but on iOS it seems to be the kind of thing developers find interesting – creating simple apps for only 59p."

iPad for all

The benefit of the school's 'iPad for all' philosophy is particularly evident in art. Brushes is popular, as are quirkier apps such as TypeDrawing (where you fingerpaint with letters); most importantly, though, instead of replacing traditional media, the iPad has given pupils newfound confidence in all areas of art.

"The iPad is not a substitute for existing media, and it requires artistic skill to master, but in some ways it more effectively helps pupils develop confidence in their abilities and enthusiasm to try," asserts art teacher Jenny Oakley. She says a combination of immediacy, security (due to 'undo') and usability means pupils "do not have to overcome the hindrance of learning to manipulate another tool – rather, they use one they've developed dexterity in since birth".

With this newfound confidence, pupils are more willing to try, which Oakley says is "half the battle". The iPad also provides assistance regarding experimentation – pupils can use filters and effects to visualise how something would look in a different medium and then use real-world tools to mimic what they see on the screen.

The move to digital

While it's clear Cedars School of Excellence has integrated iPads into the learning environment, critics remain concerned; they claim the school's pupils are being denied access to technology that would supposedly prepare them for the real world and that 'everything' is being replaced by electronic content. Such inaccurate statements annoy Fraser:

"In reality, we're sometimes using the iPad exclusively and sometimes not. Truth be told, I'd like to move to the iPad more, but we're constrained by resources – some textbooks aren't available electronically, for example. Anyone against such iPad use should bear in mind that society itself is in the process of replacing everything with electronic content – it's happened with CDs, and Amazon and Apple are doing the same with books."

Fraser adds that a child starting school today won't leave until 2023, by which point, who knows what technology will be commonplace? His thoughts are the same regarding anyone who says children should solely work on Windows PCs – instead, he argues that they should use whatever tools enable them to best learn: "The iPad beats a PC because it removes that whole layer of 'we're doing computers now', and you end up with 'we're doing maths' or 'we're doing music'."

The iPad also eliminates some of the menial aspects of schooling: "In traditional teaching, you spend time learning how to write a sum properly, how to lay out a jotter, how to lay out text on a page. You must do that before you can express thoughts and ideas. But with an iPad, open Pages and you can immediately start writing an essay or play."

This is why even if a Mac OS X tablet arrived, Fraser wouldn't switch, and he thinks the same regarding the recent slew of iPad wannabes. "There's something about the iPad's size that's just right – make it a 7-inch widescreen and the keyboard would be tiny, but the iPad's screen enables you to have a good-sized keyboard and see your content. Also, the form factor enables you to have a long-lasting battery," he says.

And while iPad competitors brag about hardware, Fraser says that's irrelevant: "As good as the iPad's hardware is, it's the software that makes the device interesting in education – and I'm not just referring to big brands, but to small apps as well."

User focus

The reality of using a platform that focuses on what you can do with it rather than what's under the hood has resulted in focused pupils. Fraser says teachers throughout the school are finding that pupils now just get on with tasks, "because they have some way of working that's not just 'write it down on a piece of paper' – schooling has become more flexible and therefore more engaging and interesting."

Fraser nonetheless admits that the speed of adoption and the 'invisible' nature of the technology has surprised him: "We didn't think the iPad would become embedded quite so quickly. Already, it's a problem if a child forgets their iPad – in fact, on the day of the interview, one pupil did just that and convinced his mother to drive his device to the school.

"It's funny, because we'd had this idea about disciplining a child by taking away their iPad, but doing that would break someone's school day, because we now operate under the assumption that digital technology is as available as paper!"

Fraser adds that it's also crucial to consider the technology 'everyday' and not 'special'. "For example, it's important to not use the iPad as a reward. Technology is the way we do business – it's how we teach. It's not a reward for doing traditional education well."

Although using an iPad is simple, setting up the school's system was anything but for Fraser, and limitations in Apple's ecosystem soon became apparent.

The school currently has an Xserve providing user-login services to iMacs and notebooks, and Fraser's "beloved" iMac suite was dismantled, to enable each classroom to house an iMac. Each morning, pupils log in to accounts to sync their iPads with their class's iMac.

Secondary pupils each have their own library, enabling a certain amount of customisation (such as podcast subscriptions); in primary, every iPad is synchronised to the same account.

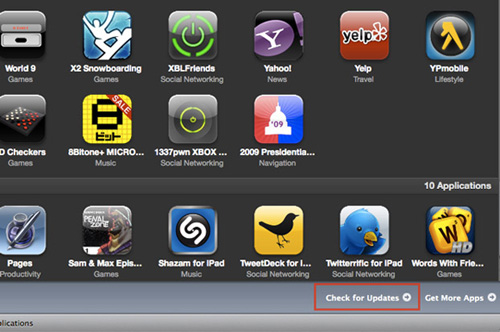

In terms of app purchase and deployment, Fraser buys apps on his computer and copies them elsewhere via Home Sharing. "This doesn't do updates, so teachers have to press 'update all' on some iPads each day," says Fraser. And due to the lack of app volume purchasing in the UK, the system requires a certain amount of jumping through hoops, in order to ensure developers get their fair share.

"No iTunes account can buy an app more than once, and it would take too long to create an account for each pupil. Also, no-one under 13 can have an account, unless it's set up by a parent or guardian," explains Fraser.

His devised workaround is the use of 'gifts' apps to dummy email accounts at the school, which are not accessed, so the right number of apps is always purchased; nonetheless, it's clear Fraser is hopeful when he says "there are better times ahead" regarding this part of the project.

The downside

Elsewhere, problems exist. Due to leasing iPads from the Apple Store, faulty units are replaced with ease, and on-site spares ensure pupils end up with just 30 minutes of downtime while their content is synced to a replacement. (Fraser discloses the iPads have so far proven durable, and the only two major faults have been down to commonplace screen failures.)

Even the thorny issue of funding never became a block. The school funds the iPads out of its general budget, and with it being an independent school, Fraser says the portion from fees that goes towards iPads is "a mathematically provable trivial fraction"; furthermore, savings made elsewhere (less printing, mostly sleeping iMacs, fewer book replacements) are already starting to offset the relatively small iPad leasing fees.

Whether there's a wider future for the iPad in the classroom remains to be seen. Fraser thinks many aspects of his project are scalable, to state schools as well as independents, but local authorities and a lack of administration tools are likely to be stumbling blocks.

He notes that "magic money" (from election years or companies looking for favours from councils) often pays for school technology, but computers end up being mothballed when there's no funding for a refresh. Also, money disappears into systems that teachers don't ask for, such as interactive whiteboards. Therefore, it's "policy that usually dictates whether something is 'possible', rather than the benefits, drawbacks and limitations of a system".

On administration tools, Fraser says Apple needs to devise something for schools with larger classes (Fraser's school has classes with as few as a dozen pupils, rather than the UK average of 25), particularly regarding remote inspection facilities:

"With a small class, I can walk around and see what everyone's doing, but that would be hard with twice as many pupils." He'd like to see Apple-enabled iPad administration and access through Apple Remote Desktop, for pulling browser histories over the air, updating apps, locking devices and capturing screens, but without a system administrator having to pay for enterprise-grade infrastructure.

Time to relax

On the software side, at least, things are better; Fraser says he's having the quietest time he's ever experienced as the 'IT guy' at school, despite having multiplied by five the number of deployed devices he's responsible for.

Next he's keen to assist teachers who are less confident about using iPads by figuring out how and why some teachers are speeding ahead and helping everyone get to the same level. "I'm trying to move on the pupils' minds too – in class, someone will ask if they can go online to find something. I'll say of course – as long as it's relevant, use whatever you want."

Perhaps it will be a while before everyone's fully comfortable with iPads in the classroom, but then Fraser says that's hardly surprising, given that classrooms worldwide remain largely traditional, and technology is usually prescriptive:

"We've done something that's not often tried – we brought in technology and didn't tell people how to use it". Instead of thinking of the iPad as a digital textbook, it's become a research and creativity tool across all subjects; because of this, minds are being expanded and experiences broadened, not restricted. Once, the school focused on iWork, iLife and Safari, but now pupils access dozens of varied apps.

"Apple pundit John Gruber once described the iPad as an app console, and I think he's right. It's something for doing work on or playing games – but it's not a generalised platform," says Fraser as the interview concludes.

"That's good for me, because I want kids to learn – I don't want them to work through the computer stuff just to get to the learning." We think that should be enough to silence his critics.